<< Back to Media

COVID-19 Underscores Need for Data Philanthropy

June 12, 2020

Not every company will give away its work for free. But when the COVID-19 pandemic first struck, the Virginia-based data science company Fraym understood its unique product was critical in mounting the most effective global COVID-19 response at scale. The company put out an offer to distribute its data for free — an action commonly referred to as “data philanthropy” — and asked anyone, anywhere how it could further help.

Within a few weeks Fraym placed life-saving data into the hands of 11 countries and 40 organizations, including health ministries, local disease control agencies, private sector companies, and local and international non-government organizations.

“In the early days there was a very quick and collective desire to help, to support, to find a way to get the data we produce into the hands of frontline responders,” said Fraym’s CEO, Ben Leo.

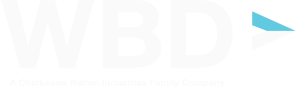

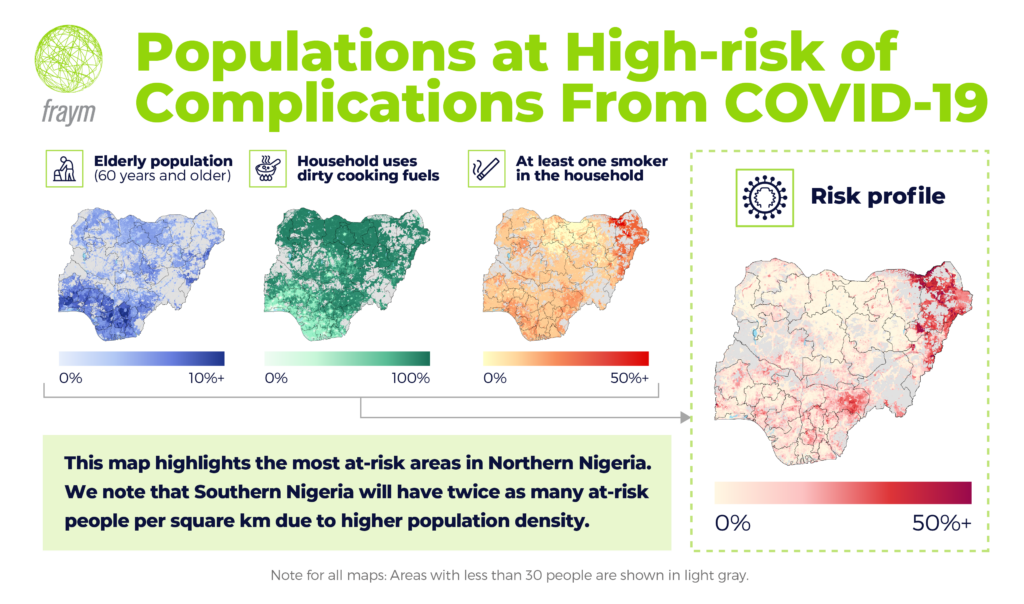

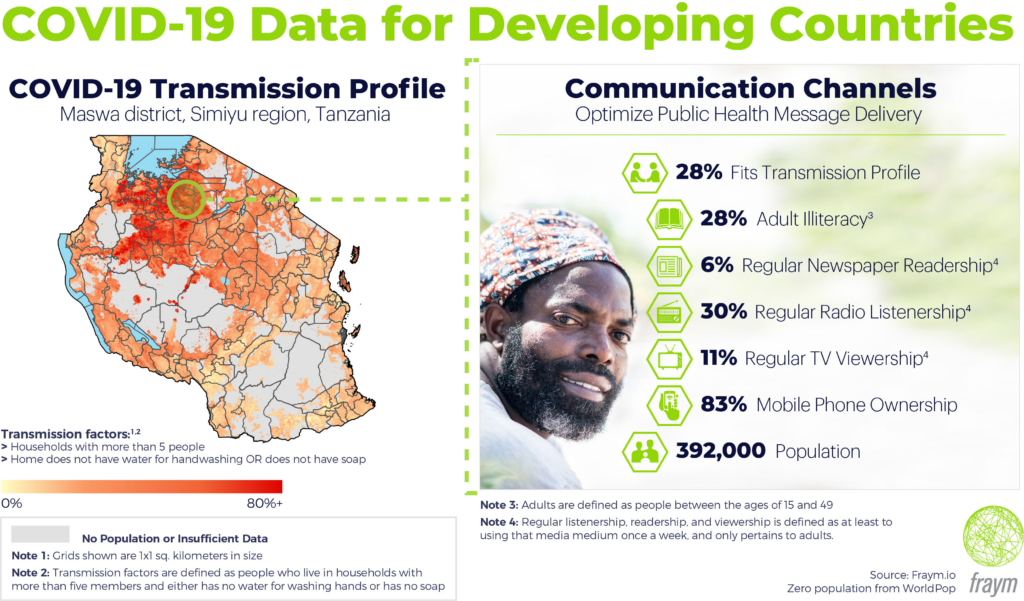

And not just ordinary data, but highly localized information based on the responders most acute need: Where will the concentration of risk be highest? Where’s the greatest likelihood of transmission across the developing world?

Back in early 2020, Fraym looked at the media and epidemiological reports and began organizing relevant data they knew frontline responders would need. Then in mid-March, the company put out the open call to access its data free of charge.

“We need to have the best information at the most localized level so that we can inform our strategies, our prevention activities, as well as the response activities to place the scare resources where they can have the greatest impact,” said Leo on producing and distributing its COVID-related data.

Not All Data Are Equal

Fraym is unique among data science companies for its ability to collect hyper-localized data in its geospatial capabilities. Unless there’s specific data on target groups across an entire region or country — such as villages or a neighborhood’s access to a specific service and their ability to pay for it — then the information is worthless and could even be harmful because it assumes everyone looks and acts the same across a coarse aggregate statistic.

“We are able to tell you what a neighborhood looks like across 100 unique characteristics from their demographics. These neighborhood statistics that Fraym produces at scale on a very fast basis can inform strategic and tactical decisions,” said Leo.

Fraym set out in 2015 to bridge such gaps and identify target population groups and understand the context in which they’re living to then inform a strategy, an investment, a project, a program.

For COVID-19 responders, that kind of data has saved lives.

How Fraym Does It

Fraym’s unique contribution to the data science field stems from the geospatial data production processes they have built, refined, and continue to improve on a continuous basis to produce hyper-localized data at scale across the developing world. Their ability to produce this hyper-localized data stems from a confluence of improvements in three spheres:

- Satellite imagery with high refresh rates that are widely accessible

- Cloud computing that can quickly compute massive amounts of data

- Geo-coordinated or geo-tagged household survey data from a variety of sources

Once the data meets Fraym’s quality standards, the three core ingredients and other remote-sensed features go into the company’s advanced machine learning algorithms or enable those algorithms to be produced and used at scale. Then there’s a quality assurance and validation process before the data and its sources are provided to Fraym’s partners.

One of Fraym’s partners is the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). Fraym provided the USAID mission in Kenya, and many other USAID missions, with data to inform preexisting USAID projects and programs including USAID support to the Kenyan government’s planning and activities. Leo also noted that USAID is one of the biggest supporters of ensuring that high-quality, professionally enumerated, geo-tagged survey data is produced across the developing world.

The data supplied by Fraym supports the new USAID Digital Strategy 2020-2024: “a deliberate and holistic commitment to improve development and humanitarian assistance outcomes through the use of digital technology.” The digital strategy at USAID contributes to “measurable development and humanitarian-assistance outcomes” through “open, secure, and inclusive digital ecosystems” all aimed to increase self-reliance in its partner countries.

“A Million Acts of Generosity”

Fraym expected that governments and non-government donor agencies would respond to its open call for data assistance, but the numerous requests from the private sector who were trying to help their country’s government or health ministry office in its COVID-19 response surprised them.

“It was a million acts of generosity in collectiveness that was very, very impressive,” said Leo.

Fraym provided many private enterprises with data to relay formally and informally to their respective governments. And in Nigeria, Fraym worked with its government in real time to help them make sense of the raw data they were providing and use it to generate insights.

“This data science revolution is unfolding in front of our eyes and it’s incredibly important to be able to meet individuals and organizations where they are today, with the most useful information that helps them do their job better, faster, or more effectively,” said Leo. “Sometimes it’s raw data, sometimes it’s just the insight, and sometimes it’s a combination of the two.”

Regardless, Leo emphasized, data science companies collectively, and not just Fraym, must “meet them where they are instead of where we hope they would be or where they might be in five years.”

The Months Ahead

As Fraym gets a handle on different kinds of downstream effects, Leo sees situations that are unfolding and changing rapidly.

“One of them in particular is the breadth of food security challenges in urban areas. We haven’t seen these kinds of implications at the scale that we’re seeing now very much in the past.”

Typically, Leo said, food insecurity in rural areas is climate- or conflict-driven, and it’s been a supply shock or market access shock. In urban areas, food insecurity usually results from price hikes due to a supply chain problem or a global economic or importation issue. But he emphasized, “With this pandemic, the value and supply chain have been disrupted in profound ways. It’s not just simply a pricing issue, but there are accessibility issues that we don’t usually see in this way at this scale very often historically.”

Leo expects Fraym will be focused for many months on data surrounding the pandemic’s second-order impacts to inform humanitarian and food assistance or other kinds of programmatic activities as it continues to help partners be as effective as possible.

“For Fraym and for others this is a clarion call, yet again, for the need for localized data.”

…

The article above was created by our Private Sector Engagement Mechanism team to support our client at USAID. Here at Washington Business Dynamics, our team also harnesses cutting-edge technologies to assist organizations in transforming their culture, performance, or processes. We recognize the potential of digital innovation. We use advanced analytical tools to research and formulate solutions and display our findings to clients through intelligible mediums. Furthermore, we harness these cutting-edge technologies to assist organizations in building their own systems with the incorporation of advanced data-analytic capabilities. By taking a holistic approach to artificial intelligence, our team ensures that our clients are able to take advantage of technological innovation.